I Didn't Know What Posthumous Meant

1. Why posthumous should mean posthuman

I always assumed posthumous meant post human. Researching the etymology of the word, I discovered that its origins are far more murky than this, with borrowed language intermingling to create a phrase that vaguely refers to the act of burial—the Latin root, humus, means earth—voila, post dropping into earth:

The etymology of the word posthumous tells a complex story. In Latin, posterus is an adjective meaning "coming after" (from post, meaning "after"). The comparative form of posterus is posterior, and its superlative form is postumus, which means, among other things, "last." Postumus had specific application in referring to the last of a man's children, which in some cases meant those born after he had died. Latin speakers incorrectly identified the -umus in this word with humus, meaning "dirt" or "earth" (suggesting the ground in which the unfortunate father now lay). The Latin spelling became posthumus, as if the word were formed from post and humus, and both the "h" and the suggestion of "after burial" or "after death" carried over into English. (Merriam Webster)

After burial, the slow bureaucracy of the earth takes charge; the detritivores enact mouth-to-flesh paperwork in the soil, signing documents of reclamation. This is the posthumous of the grammarians: the sensible, well-tended plot, an etymology with ordered lineage. This is banal. Banality is disappointing; it induces weeping.

Still, there is value in my confusion. Language is a big pot of steaming soup that we dare to dunk our hands in, adding more bacteria to the festering incoherence. In fact, my misinterpretation aligns with the origins of folk etymology; like the Englishmen of yore, I contributed to the contamination. So I shall entertain the contaminated notion that the word ‘posthumously’ captures the essence of a posthuman, since semantic misinterpretations often reveal the giant bugs that lurk beneath the boulder of objective meaning.

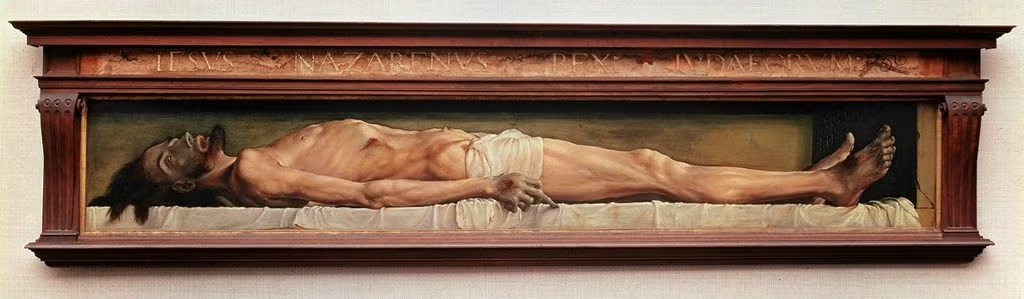

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, Hans Holbien

2. The uncomfortable posthuman

Let us, then, delve into the posthuman, a much more fascinating kind of terrain. A posthumous award, promotion, or even the act of posthumous recognition itself, is more than an acknowledgement of one’s achievements. In some cases, it may have a practical effect—posthomous military promotions, for example, can give relatives of the deceased some form of financial compensation—but even then, there is a symbolic quality to these posthumous accolades, otherwise they would have no reason to exist once the subject is no longer there to receive them. Posthumous recognition operates within a realm where presence is defined by cultural memory as opposed to physical being. The posthuman emerges when human identity is abstracted from corporeality; the fleshy cabinet dissolves to reveal the internal human project, which holds its own symbolic capital outside of the human form.

This is where the posthumous nestles into the posthuman; both are concerned with a kind of afterlife. It deals with the persistence of presence in absence, the mechanism through which bureaucratic and narrative systems continue to interact with the traces of individuals as if they were still operative subjects. The body is gone, but the name, rank, image, metadata, profiles, written works, and visual art continue to circulate, producing effects in the world.

Of course, we should not be naïve enough to assume that the posthuman is a natural continuation of human existence. There is something unnatural, even unsettling, about an award for a dead man, an applause for a dead man. Through these actions, we shoot an arrow of recognition into heaven. We project our need for continuity and endless meaning onto a non-participant. Much like an arrow shot upwards inevitably returns to its sender, the applause reverberates within the hearts of the living. And, most interestingly, the posthumous award, though received by an absence, has a tangible effect on the world of the living (an insignificant posthumous award can still alter a narrative or influence a perception; a significant one might even shape policy.)

What do we truly recognise in the posthumous? Is it the individual themselves, or the values the deceased came to represent? And if the latter… Why the award? Why do we reach for an answer that remains unspoken by the dead? Are we attempting to answer on behalf of the dead?

Look, I don't want to be a hyperrationalist, nor an antisentimentalist. I won’t deny that there is clear value in symbolic acts, which help us make sense of loss and absence. They speak to our desire to believe that meaning doesn’t die with the body; that human effort and achievement can persist in the form of memory. But we must ask ourselves what this reveals about our relationship to both life and death. Posthumous recognition, though pointed outwards, reveals the discomfort in ourselves. It represents the infinite envy of the dead (they have transcended the flesh, and so we must venerate them) and the infinite dread (they have transcended the flesh, and so we must pull them back with our awards.) The arrow we shoot into heaven acts as a tether we hope might yank the departed back into our field of vision, if only for one more speech.

Christ on the Cross, Guido Reni

3. The idealised posthuman

The posthuman takes another shape that I would like to explore. In this light, both posthumous recognition and the posthuman are venerated because they allow us to escape the discomfort of the human body. O that this too solid flesh would melt and resolve itself into dew!; For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality; The body is the tomb of the soul; Human, All Too Human. The body recoils from itself. Even the new-age Starseeds, who are incessantly mocked, are a reflection of the same cultural pattern: our desire to escape the humdrum and messiness of being. We are disgusted by the human brain (yes! even the brain, which is distinct from the soul) and the human body; it is what lingers between that we identify with. If we appropriate Deleuze and Guattari’s “body without organs” to fit my schema (a term fit for appropriation due to its ambiguity… that boulder of objective meaning…) , we can see how this notion fits: we dissociate from the corporeal because it is so perverted in its vulnerability. We look away from blood and piss and shit and everything else. We paint the faces of our corpses pretty just to look away.

But we cling to the soul—that indomitable spirit from which everything flows—because the soul gives us permission to be human. It is the souls of those great dead figures that we cover with awards, while their corpses dissolve in the dirt. These mythologised figures become more than human, elevated to the status of immortal gods.

(I have noticed that, at least with literary greats, this mythologisation inevitably removes from one's understanding of the work. This is why English classrooms make children hate Shakespeare (unless the autistic-about-Shakespeare gene is already present in the child.) When one excessively elevates a figure, they stop seeing the humanity in their work. Shakespeare becomes a monument whose works we must revere from a distance. The irony is that the more we dehumanise him, the less accessible his creations become. Shakespeare was as flawed and fucked up as any writer, but in our need to preserve him as untouchable, we lose the very essence that made his work resonate with the human condition. Anyways,)

The posthuman becomes a perfect image of what we could be if we were free from the constraints of the physical world, liberated from the filth that taints us. The posthuman is the beauty of death. According to Bladee,

Death is beautiful, death is beautiful, death is beautiful (Life)Death is beautiful, death is beautiful

We think we exist, that’s why we suffer, do we not? (Do we not?)

The posthuman is the urge to revere the transcendent and reject the mundane. By looking beyond the body, we escape our present existence. We want to transcend the very thing that makes us human, even though this imperfection may be the stronghold of our meaning. And so we shoot an arrow of recognition into heaven.